Die Argumentation der internen Fluchtalternative wird derzeit inflationär von den Behörden verwendet. Dass es sich dabei um keine neue Strategie der Behörden handelt, zeigt schon die Richtlinie der UNHCR zur „Interne Flucht- oder Neuansiedlungsalternative“ aus dem Jahr 2003. Die Einleitung beginnt mit den Sätzen:

„Die interne Flucht- oder Neuansiedlungsalternative (internal flight or relocation alternative) ist ein Konzept, das von Entscheidungsträgern in zunehmendem Maße bei der Feststellung der Flüchtlingseigenschaft herangezogen wird. Bis heute gibt es diesbezüglich keine systematische Vorgehensweise, was dazu geführt hat, dass diese Frage sowohl innerhalb als auch zwischen den Rechtsordnungen unterschiedlich gehandhabt wird. „

Und wie unterschiedlich das gehandhabt wird, möchte ich anhand eines UNHCR Dokuments vom März 2018 „Internationale Schutzbedürfnisse von Asylsuchende aus Afghanistan“ und den Argumentationen der Behörden aufzeigen.

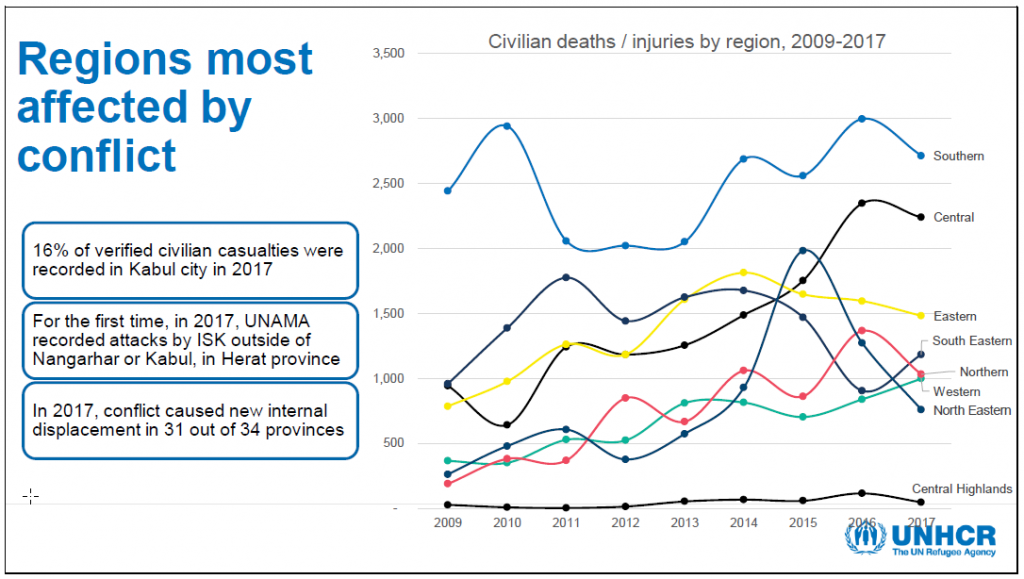

- While civilians in the Southern Region have consistently suffered the highest number of casualties since 2009, the Central Region (including Kabul city) has seen a dramatic rise in the number of civilian casualties since 2014, becoming the second most dangerous region of Afghanistan for civilians in 2016 and 2017.

In Österreich sind allerdings die Zahlen für subsidiären Schutz seit 2016 dramatisch zurückgegangen, obwohl sich die Sicherheitslage verschlechtert hat.

Das hängt auch mit dem Mahringer Gutachten zusammen. Aber man darf dem Herrn Mahringer nicht zu viel Bedeutung zuschreiben. Es gibt ja auch noch den „Joint-Way-Forward“ Deal zwischen der EU und Afghanistan.

TODO

- Neither Kabul nor Herat city were safe for civilians in 2017, with both cities reporting hundreds of civilian casualties (Kabul city > 1,600, representing a 17% increase compared to 2016).

Ganz klar sieht Österreich die Sache anders. Ist ja auch kein Wunder wenn wir den Herrn Mahringer als offiziellen Austria-Scout haben, um uns zu berichten wie es denn in Kabul oder Herat so zugeht. Damit wir dann mit Hilfe des Austria-Escort die Leute dann dorthin bringen.

- If internal relocation is to be considered, a particular area must be identified by the decision-maker, and the claimant must be provided with an adequate opportunity to respond in the interests of procedural fairness.

Mit „procedural fairness“ nehmen wir es ja nicht so genau. Aber der Asylwerber kann schon sagen, dass es in Kabul für ihn nicht sicher ist – das war es dann auch schon.

Wenn er Glück hat wird ihm dann mitgeteilt, dass man schon weiß, dass es in Kabul sicherheitsrelevante Situationen gibt, diese seien aber nicht gegen den Asylwerber gerichtet und daher OK.

- The relocation alternative must be more than a “safe haven” away from the area of origin.

TODO

- The personal circumstances of an individual should always be given due weight in assessing whether it would be unduly harsh and therefore unreasonable for the person to relocate in the proposed area. Of relevance in making this assessment are factors such as age, sex, health, disability, family situation and relationships, social or other vulnerabilities, ethnic, cultural or religious considerations, political and social links and compatibility, language abilities, educational, professional and work background and opportunities, and any past persecution and its psychological effects. In particular, lack of ethnic or other cultural ties may result in isolation of the individual and even discrimination in communities where close ties of this kind are a dominant feature of daily life.

TODO

- In Afghan society, living alone is assumed to be negatively associated with inappropriate behavior; eg. the consumption of alcohol or illicit relations. This perception applies to both women and men. Consequently, Afghans without family or an established community network could not reasonably relocate to Kabul or other cities.

Die personellen Umstände sind während der Verfahren scheinbar nur deswegen von Interesse, um das Vorhandensein einer Familie festzustellen, die dem Rückkehrer ein soziales Netzwerk und Unterstützung bieten kann. Daher auch die immer wiederkehrende Frage nach den Familienmitgliedern in der Heimat.

- The deteriorating security situation and lack of absorption capacity pose significant reintegration challenges for returnees and IDPs. Key protection risks include lack of access to adequate shelter, healthcare, education, and documentation; lack of viable livelihood opportunities resulting in negative coping mechanisms (e.g. exploitative working conditions, child labour, early or forced marriage, debt); threats of violence and forced recruitment by AGEs; and death or injury from improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and explosive remnants of war (especially among children).

Nicht so die Argumentation des BFA. Hier finden wir in Bescheiden folgende Rechtfertigung für eine Abschiebung. „Hinzu kommt, dass in Afghanistan komplementäre Auffangmöglichkeiten, etwa in Lagern, existieren, die Sie im Falle einer erfolglosen Suche nach einer Unterkunft in Anspruch nehmen könnten. Sie könnten demnach selbst dann, wenn Sie entgegen der behördlichen Feststellung, dass Sie keiner Gefährdung im Sinne der GFK ausgesetzt sind, doch aus wohlbegründeter Furcht Ihre Heimat verlassen haben sollten, insbesondere in Kabul Sicherheit und zudem zumutbare Lebensbedingungen vorfinden.“

- Further, the conflict has limited humanitarian access and the delivery of assistance, thus returnees and IDPs in hard to reach areas, including areas controlled or contested by AGEs, face even greater vulnerabilities. UNHCR has found modalities, such as national partners and liaison officers who facilitate communication with beneficiaries, protection monitoring, and access in hard to reach areas to the extent possible. Telephone surveys also support the collection of information on the affected population’s protection concerns, through representative sampling (eg. ODR).

- NB: explain that UNHCR provides repatriation assistance to only those refugees that repatriate voluntary, which means that deported individuals and failed asylum seekers do not benefit from this assistance! Assistance includes overnight accommodation, an unconditional cash grant of approximately USD 200 /individual to meet their immediate needs for transport, food and shelter, vaccinations and basic health screening, and mine risk education and awareness. Afghans returning from Europe (voluntarily or otherwise), who were not found to be in need of international protection and therefore refused asylum or subsidiary protection, are not monitored by UNHCR upon their return to Afghanistan as the sending country has deemed they are not refugees.

Ob man das in Wiener Neustadt und den anderen Außenstellen des BFA weiß. Nur freiwillige Rückkehrer bekommen Unterstützung von der UNO. Wenn also jemand partout der Meinung ist in Kabul nicht sicher zu sein und sich nicht freiwillig zu einer Rückkehr entscheidet, so ist ihm die Unterstützung der gelobten Lager nicht zugesagt.

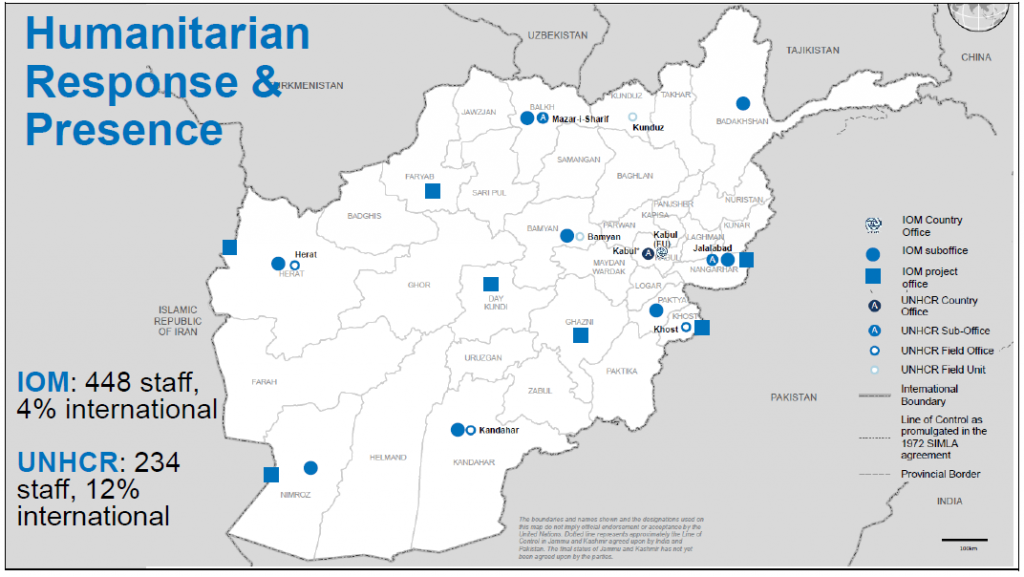

- IOM and UNHCR work in in close partnership, along with government ministries, other UN agencies, NGOs and local communities to provide humanitarian protection through return and reintegration support for registered refugees who voluntarily repatriate (UNHCR) and other Afghans returning either voluntarily or involuntarily (IOM). Community-based protection measures include several small-scale livelihood initiatives and vocational training, designed as a catalyst to link beneficiaries with longer-term development projects.

- IOM has established reception centres at the 4 major border crossings (Torkham, Spin Boldak, Islam Qala, Milak) and a network of transit centres near borders or in major neighbouring cities. IOM assists 95% of returns from Pakistan, but only 4% of returnees from Iran due to funding constraints, targeting the most vulnerable PSNs and their families, eg. urgent medical cases, victims of trafficking, and unaccompanied children. For Afghans returning from Europe, IOM and MoRR provide temporary accommodation for up to 2 weeks in Kabul.

- UNHCR leads the Protection Cluster and Emergency Shelter/NFI Cluster, in coordination with humanitarian partners, as part of the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP).

- UNHCR also leads the response to address the needs of an estimated 100,000 Pakistani refugees from North Waziristan Agency (NWA), providing targeted assistance to persons with specific needs (PSNs) and building capacity, self-reliance and resilience through livelihood initiatives, while coordinating with government authorities and partners to ensure continuity of essential services including basic health care, WASH, and education. In addition, UNHCR provides protection and assistance to almost 500 refugees and asylum-seekers of various nationalities residing in Kabul, Kandahar and Herat, registered under the UNHCR mandate in the absence of a national refugee law.

– 58,592 registered Afghan refugees returned to Afghanistan in 2017 from Pakistan (98%), Iran (2%) and other countries. - The rate of return, compared to 2016, for registered refugees and undocumented Afghans substantially decreased, largely as a result of an improved protection environment for registered Afghan refugees in Pakistan as well as the undocumented population.

- IOM reported more than 400,000 returns from Iran and Pakistan of other Afghans who were not registered as refugees, although many returns from Iran represented a cycle of repeated cross-border movements.

- The majority of arrivals from Iran had left Afghanistan less than 6 months before their deportation or spontaneous return, and many had not had effective access to asylum procedures.

- Afghans displaced within the last 10 years are not able to obtain a PoR card in Pakistan, while Amayesh cards in Iran are only renewed for Afghans who were first registered pre-2002.

- UNHCR advocates on behalf of the undocumented population in both Pakistan and Iran to maintain protection space and ensure access to asylum or registration procedures (eg. 2017 headcount exercise in Iran, ACC registration in Pakistan).

- Each year, 400,000 Afghans enter the labor market and less than half find work. Many work for only a few days a week or month. Establishing a business is not realistic for individuals with no training, entrepreneurial skills, or experience, even if given financial capital. The majority of Afghans rely on daily wage labor – those who lived in urban environments in Iran or Pakistan will not easily adapt to agricultural labor, while construction and laboring job opportunities in urban cities are not sufficient to meet demand.

Und was sagt der Mahringer:

Der lntegrationserfolg eines Rückkehrers in den Städten Kabul, Mazar-e Sharif und Herat hängt ausschließlich vom Willen des Rückkehrers ab. „

oder

„Die Verdienstmöglichkeiten für männliche Rückkehrer ohne soziale/familiäre Anknüpfungspunkte sind ohne Einschränkung in den Punkten a) [ohne Schuldbildung oder Berufserfahrung] bis c) [fundierter Schulbildung und Berufserfahrung] gegeben.„

oder

„Viele Organisationen bieten bereits Arbeitsplätze über das Internet an. Fast alle Arbeitsplätze, der internationalen Gemeinschaft, für Afghanen werden öffentlich übers Internet angeboten.„

oder

„Afghanistan hat auch ein Gesetz für einen Mindestlohn. Dieser beträgt zurzeit Afghani 5000 (entspricht am 2/20/2017 ca. 75$) monatlich und gilt nur für Arbeiter im öffentlichen Sektor, der private Sektor hat keinen Mindestlohn, wobei aber im Arbeitsrecht vorgesehen, ist das der Lohn für Arbeiter im privaten Sektor nicht kleiner sein soll als für Arbeiter im öffentlichen Sektor.“

oder

Arbeitserfahrungen sind auch in Afghanistan ein Vorteil bei der Arbeitssuche wobei, viele Unternehmen die Erfahrung machen, das Rückkehrer zu hohe En/vartungen hinsichtlich des Einkommens und ihrer Kenntnisse haben. Mehrere Gesprächspartner aus der Wirtschaft berichteten von Erfahrungen mit Rückkehrern. Deren Erfahrung ist, dass Rückkehrer ihre Unterstützung im Ausland ohne Arbeit, vergleichen mit den afghanischen Lohn und damit argumentieren warum sie für einen so geringen Lohn (afghanischer Standard) arbeiten sollten, wenn sie im Ausland ein mehrfaches ohne Arbeit bekommen.“

oder

„Es gibt auch die Möglichkeit für Rückkehrer ohne Ausbildung, die staatlichen Behörden

stellen viele Mitarbeiter mit geringer oder keiner Qualifikation zum Mindestlohn an. Des Weiteren gibt es eine Vielzahl von Arbeitsmöglichkeiten im privaten Sektor. Arbeitsmöglichkeiten für minderqualifizierte Rückkehrer bedarf besonderer Anstrengungen der Arbeitsuchenden..„

- 40% of population suffers food insecurity (OCHA)

Und was sagt der Mahringer?

Alles paletti – und zum Grillen gibt’s auch genug Fleisch.

- 41% of children < 5 years old are stunted, 25% are underweight

- Over 34% of the working-age population are either unemployed or underemployed

- Almost 40% of the Afghan population live in poverty

- Despite the establishment of the 2008-2013 National Social Protection Strategy, government social protection in Afghanistan remains very limited, with children and women-sensitive social protection almost non-existent. Afghans rely entirely on their family and networks as a safety net.

- For IDPs and returnees, the presence of a social network is fundamental in the choice of their destination, as relatives are the primary sources of support and economic assistance, and security. Returning refugees, IDPs and deportees often lack social networks in the area of displacement or return, however.

- There is a misperception that poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion are predominantly rural concerns in Afghanistan. In reality, however, since social safety nets, access to land, and subsistence living of rural areas are not available in cities, urban dwellers frequently find themselves without coping mechanisms, at heightened vulnerability.

- In 2016, for the first time, urban areas are more food insecure than rural areas. As a result, urban households are more likely to resort to emergency or negative coping strategies such as begging, selling their house or land, or migrating. This is due to rising unemployment and under-employment levels in urban areas, as well as the continuing rural to urban migration flows, partly fueled by the rise in IDPs. Nepotism and bribery affect access to employment, especially for women. Without intermediaries it is difficult to get a job with the government or NGOs.

- Kabul Informal Settlements (KIS). There are about 50 such camps around Kabul hosting mostly IDPs, returnees, and ethnic minorities – Kuchi or Jogis. Most KIS inhabitants live in slum-like conditions. Their shelters do not provide sufficient protection against the cold and wet winter months, are over-crowded and do not provide sufficient privacy. In many locations a large number of families share only a few hand pumps to access clean water. The population lives under constant threat of eviction. Access to basic services and public infrastructure is very limited. Kabul was initially built for 500,000 people, now 75% of the city consists of informal settlements.

- Significant ethnic segregation in major cities, despite diversity of population.

- Sources: WB, CSO, EASO

- Each year, 400,000 Afghans enter the labor market and less than half find work. Many work for only a few days a week or month. Establishing a business is not realistic for individuals with no training, entrepreneurial skills, or experience, even if given financial capital. The majority of Afghans rely on daily wage labor – those who lived in urban environments in Iran or Pakistan will not easily adapt to agricultural labor, while construction and laboring job opportunities in urban cities are not sufficient to meet demand.

- Despite the establishment of the 2008-2013 National Social Protection Strategy, government social protection in Afghanistan remains very limited, with children and women-sensitive social protection almost non-existent. Afghans rely entirely on their family and networks as a safety net. For IDPs and returnees, the presence of a social network is fundamental in the choice of their destination, as relatives are the primary sources of support and economic assistance, and security. Returning refugees, IDPs and deportees often lack social networks in the area of displacement or return, however.

- There is a misperception that poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion are predominantly rural concerns in Afghanistan. In reality, however, since social safety nets, access to land, and subsistence living of rural areas are not available in cities, urban dwellers frequently find themselves without coping mechanisms, at heightened vulnerability.

- In 2016, for the first time, urban areas are more food insecure than rural areas. As a result, urban households are more likely to resort to emergency or negative coping strategies such as begging, selling their house or land, or migrating. This is due to rising unemployment and under-employment levels in urban areas, as well as the continuing rural to urban migration flows, partly fueled by the rise in IDPs. Nepotism and bribery affect access to employment, especially for women. Without intermediaries it is difficult to get a job with the government or NGOs.

- Kabul Informal Settlements (KIS). There are about 50 such camps around Kabul hosting mostly IDPs, returnees, and ethnic minorities – Kuchi or Jogis. Most KIS inhabitants live in slum-like conditions. Their shelters do not provide sufficient protection against the cold and wet winter months, are over-crowded and do not provide sufficient privacy. In many locations a large number of families share only a few hand pumps to access clean water. The population lives under constant threat of eviction. Access to basic services and public infrastructure is very limited. Kabul was initially built for 500,000 people, now 75% of the city consists of informal settlements.

- Significant ethnic segregation in major cities, despite diversity of population.

- Sources: WB, CSO, EASO

- Wealthier people travel abroad for medical treatment, mainly to Pakistan or India. Limited medicines available in Afghanistan. Despite an overall increase in the number of female health professionals, there is still a shortage. This is one of the primary access challenges for women. Dominance of an unregulated private health sector. Costs can be punitively high and quality is unpredictable due to insufficient regulation.

Source: Health Cluster, MoPH

Und was sagt der Mahringer?

„Die allgemeine Versorgungslage und allgemeine Infrastruktur ist in Summe als

befriedigend zu bewerten. Alle notwendigen Infrastrukturen sind im ausreichenden

Umfang vorhanden und es gibt keine gravierenden Engpässe und Mängel in der

allgemeinen Versorgungslage.“

„Gemäß Artikel 52 der afghanischen Verfassung von 2004 ist die medizinische Versorgung für alle Afghanen frei. Die medizinische Basisversorgung in den drei Städten – Kabul, Herat und Mazar-e Sharif ist ausreichend und für jedermann zugänglich. Krankenhausaufenthalte sind frei, privat praktizierende Ärzte verlangen Geld.„

- Primary school enrolment increased from 1 million in 2002 to over 9 million as of 2016, yet an estimated 3.5 million children remain out-of-school. Estimated 2/3 girls do not go to school.

- Only 16% of all schools are girls’ schools. Girls continue to get married early (17% before the age of 15, almost 50% before turning 18 years of age).

- 22% of children enrolled in primary schools are permanently absent. Insecurity remains a major concern for parents, who worry about the safety of sending their children to school.

- 41% of schools in Afghanistan do not have buildings.

- Sources: HRW, EASO

- State military forces and non-state armed groups used schools and universities as barracks, as sites to recruit and train children, and for other military purposes. By the end of 2016, the Ministry of Education reported that approximately 1,000 schools were closed due to insecurity, inter-communal violence, and threats from anti-government armed groups.

- Approximately 180 attacks on schools across Afghanistan were documented between 2013 and 2017. Direct attacks included arson, suicide bombings, and IEDs. Attacks on schools peaked during 2014, largely in relation to presidential elections, when non-state armed groups targeted schools used as polling stations. Parliamentary and presidential elections are scheduled to be held in 2018 and 2019, which may see renewed attacks on schools used as polling centres.

- The first eight months of 2017 saw at least 31 attacks on schools, according to media and local sources, with almost half of these attacks affecting girls’ education. The Taliban, Islamic State, and Afghan security forces were each responsible for attacks on schools, which involved mortars, airstrikes, and arson.

- In January 2017, unidentified attackers set fire to the Ahmad Shah Baba girls’ school in Kabul city, killing the security guard. The same month, Islamic State affiliates abducted 12 teachers and two administrative staff from a government-run madrasa in Nangarhar province.

- In February 2017, two students were killed when a mortar struck a classroom at Shaheed Mawlawi Habib Rahman High School, a government school, in Laghman province. At least five other students suffered injuries in the attack. Also in February, anti-government groups closed six girls’ schools in Farah province.

- 10 attacks on higher education were reported in 2016, including several high-profile attacks involving explosions, kidnappings, a beheading, and organized armed raids. A complex attack, involving suicide bombers and gunmen, took place on the American University of Afghanistan in August 2016, when armed assailants stormed the campus. Seven students, one lecturer, and two campus guards were killed in the attack.

- There were 42 verified cases of parties to the conflict occupying schools for military use in 2016, including 34 by government forces. The Ministry of Education reported in January 2017 that some 30 schools were still being used for military purposes by both Afghan government forces and anti-government groups. For example, Afghan soldiers stationed at a high school and a middle school in central Baghlan province.

- See: UN General Assembly and Security Council, “Children and Armed Conflict: Report of the Secretary-General,” A/72/361-S/2017/821, 24 August 2017: http://undocs.org/A/72/361

Und was sagt der Mahringer?

„Die afghanische Verfassung sieht ein Grundrecht auf kostenfrei Ausbildung inklusive Internate und Verpflegung vor (Grundschule) bis zum BA vor, aber es gibt keine Berufsschule; es gibt jedoch Berufsgymnasien vergleichbar unseren berufsbildenden Höheren Schulen. Es ist aber davon auszugehen, dass dieser Verfassungsgrundsatz zurzeit nur in den Städten wirksam ist.

In allen Gesprächen konnte kein Unterschied hinsichtlich der Schul- und oder Berufsausbildung in Fragen der Arbeitsmarktchancen festgestellt werden, unabhängig ob Schul- und oder Berufsausbildung, es hängt vom Einsatz des Arbeitssuchenden oder seiner Kontakte ab ob er Arbeit findet.“

- On internal protection alternatives (IFA), the actors of persecution and serious human rights violations act with general impunity, and have the ability to commit violence even in major cities such as Kabul, Herat, and Mazar, which should not be considered safe.

- There is no anonymity in Afghanistan, as new arrivals in a neighbourhood will inevitably attract interest, suspicion, and attention. The Taliban and other NSAG have extensive networks of informants (attested also in EASO report on targeting of civilians).

- It is rare for single men (and especially for single women) to live alone, which would be perceived by the local community as indicative of immoral behaviour. Individuals without existing family support or a community network would have no reliable social protection.

- International protection standards require an internal protection alternative to be both relevant and reasonable. Considering the scarce livelihood opportunities, widespread food insecurity and poverty, limited access to education, poor quality healthcare, and lack of adequate shelter and housing in Kabul, Herat, and Mazar, these cities generally would not offer a reasonable alternative to seeking international protection outside Afghanistan for asylum-seekers originating from other parts of the country.